Academy Football's

PLAN B

Academy football has developed beyond recognition in recent years. However, with more players than ever in academies, could the system be improved? Former Premier League manager Tony Pulis certainly thinks so, but what about others involved in the system?

‘We’ve all had trials, mate!’

It’s the joke that anyone who’s grown up with football would be familiar with. The notion that just about everyone could’ve been a professional footballer raises smiles, however there’s a very serious truth behind the joke. What happens to the players that are released? Have they got a backup plan to fall back on to have a successful career? Do academies provide sufficient educational support to prepare youngsters for a potential life outside of football? On average 19 in 20 academy footballers get released, a staggeringly high figure that raises serious questions about the academy model.

So, what do the stats say?

· 95% of the current 10-12,000 boys in the academy system will not have a career in the game.

· Out of the select few that make it, 78% of players who turn professional at 18 are no longer playing football within three years.

· On average 400 players sign professional terms at 18-years-old every year, but only eight of them will still be playing in the top five tiers of English football by the time they turn 22.

· What about the younger age groups? Only 0.5% of children in under-8s sides will end up making a living out of the game.

· The chance of a young boy growing up playing football in the UK becoming a professional footballer is 0.06% - that’s just six in 10,000.

It would appear that the system is designed for the select few to thrive, with many there simply to make up the numbers. That’s not necessarily the popular view of the matter, but it is the view of the man who sourced these figures; former Premier League manager Tony Pulis.

Tony Pulis

Very few people are as experienced in football as Tony Pulis; over 400 games as a player, 1,000+ games as a manager, a Premier League manager of the season award, and a lifetime of experience in the game. When someone like Tony talks, people listen.

Since leaving his last job in management at Sheffield Wednesday in 2020, Tony has finally had the time to investigate academy football’s structure and come up with a new proposal for the system. So where better to start than a trip to the legendary managers house?

Since retiring from management, Tony Pulis has been investigating ways in which academy football can improve. (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Since retiring from management, Tony Pulis has been investigating ways in which academy football can improve. (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

“Academies have changed in the respect of how big it’s got. When I started there would be two or three apprentices taken on and you’d be put in with the pros straight away. There was no break from one side and the other.

“Now you’ve got a situation where there’s under-16s, under-18s, under-21s and those teams are full of YTS (Youth Training Scheme), or apprentices or scholars. A lot of those players might have been there since just six years of age and end up having more time in an academy system than they do in school.

“A lot of these players today need to be in place to run a games programme. Clubs have a full-time games programme, never mind a full-time training programme. You need the players there to play the games every week.”

We spoke as we sat at his kitchen table with a cup of tea, just a couple of hours before his grandchildren were due to come over for a beach walk. It’s one of these grandchildren, currently in a professional academy, which gave Tony some extra motivation to kickstart his investigation into academy setups.

Tony Pulis answers some quick fire questions, with the full video available on X, Instagram and TikTok on @kyranssports

Tony Pulis answers some quick fire questions, with the full video available on X, Instagram and TikTok on @kyranssports

When Tony, 66, started as a young player at Bristol Rovers, he was involved with the pros in the first team almost immediately. There was no such thing as an academy, just a handful of scholars, a reserves team and a first team, a clear pathway that seems to have been lost as the academy system has developed.

“My issue is the fact that we know the stats say most of the kids are not going to be professional footballers. So, what can we put in place along the way to help these kids when they’re told they’re not going to be good enough.”

Tony has drawn up a plan for a dual-scholarship programme funded by the Premier League but run by an independent body that focuses on preparation for an alternative career. The UK would then be divided into six regions with teams of mentors working with young players. Tony believes that this would create a ‘safety net’ within a system where children are taken on simply to make up the numbers.

Tony Pulis on teams playing out from the back (original audio, Kyran Rickman)

“All players in academies believe they’re going to be players, they all dream they’re going to be players, they all want to be players. The hard facts are that over 90% of those players will fall by the wayside.

“I keep saying it’s like when apples fall from the tree. We know the apples are going to fall every autumn, so can we put a safety net there to stop the apples falling off and smashing their heads on the ground? Can we put a safety net for the players who are rejected and told they’re not good enough, so that they have different areas and try and place them?”

Tony Pulis took his proposals to the Premier League in 2022 and told me that an outcome is still ongoing, but he’s hopeful they’ll take his plan on.

‘When I got released at 21, I had no work experience and just a BTEC.’

These are the words of former AFC Bournemouth player Josh Carmichael. Josh, 30, was a promising midfielder in the Cherries academy, playing in the same Scotland youth setups as Aston Villa captain John McGinn and Southampton’s Ryan Fraser. However, after a handful of senior appearances, Josh was released at 21-years-old and found himself trying to find a job with just a BTEC in sport, as per Premier League education rules, as a qualification.

Josh Carmichael, didn't have the necessary qualifications for a career following his release from AFC Bournemouth (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Josh Carmichael, didn't have the necessary qualifications for a career following his release from AFC Bournemouth (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

“I went to Poole Grammar School, so I was kind of expected to go on and do A-Levels and then on to university and get a decent degree. However, compared with what I did through football is nowhere near it.

“The BTEC in sport wasn’t enough for what I wanted or could have achieved through university. A friend, who went to the same school as me, went to grammar and stayed for sixth form, got his A-levels and then got picked up by Bournemouth when they were 18. He’d had the fall-back option of three A-Levels at AAB, whereas I had a level three BTEC, and I wouldn’t say that he was any smarter than me.”

This is the issue that Tony Pulis wants to eradicate with his proposal, that when a young player gets released, they still have the necessary qualifications to get a career and not be at a disadvantage compared to someone who has never been in an academy.

Josh Carmichael on his relationship with Eddie Howe (original audio, Kyran Rickman)

“I’ve always been someone that didn’t want to stay in sport if I came out of it; I like playing it, but I didn’t want to be a sports therapist or analyst or something like that, so I had to fully start from the bottom and work my way up. Even now I’d say I’m still behind where I could have been.

“During the period of 10-16-years-old, I’d say the education support wasn’t too bad because you would catch up. However, from the age of 16+ where you’d miss out on sixth form or college and be able to work towards something you want to do, I’d say that the educational support is lacking.

“If there was an education path that I could potentially go down to get a job I wanted to do in the future, then I probably would have taken that over doing just a BTEC.”

Josh Carmichael has had a successful non-league career (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Josh Carmichael has had a successful non-league career (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Josh has had a successful non-league career, anchoring midfield in some title-winning sides, including last season at Wimborne Town. However, sitting in the Magpies impressive new clubhouse early one November evening before training, is a reminder that this is not where Josh’s ambitions would have taken him when he was making appearances in League One.

Just ten years previously ‘Shuey’, as he’s nicknamed, was a youngster at an AFC Bournemouth side which gained promotion to the Premier League for the first time in the clubs history. However, Josh wasn’t given another opportunity and was released in 2015.

“In my head I always thought I was going to be a professional footballer and even when I got released, my parents asked, ‘do you think you’re going to get another club?’ and I always said ‘yeah, no problem,’ because I was fully convinced another club would come calling.

“I think there should be more focus on a backup plan, but no one wants to focus on a plan B. When you’re in that environment no one ever thought about getting released, so it’s a tough one to implement.”

‘You’d be setting 99.9% up for a backup plan and that would take a lot of effort and a lot of money.’

To Carlisle fans, Jimmy Glass is a legend. The goalscoring goalkeeper has his unique place in football history by scoring a last-minute winner to save the club from relegation out of the Football League. After a journeyman playing career, Jimmy had ‘normal’ jobs such as a salesman and a taxi driver, before becoming AFC Bournemouth’s player liaison officer for eight years. Now, he’s Wimborne Town’s general manager, and has recently revamped the clubs academy setup.

Jimmy Glass outside of Wimborne Town FC, where he is now general manager (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Jimmy Glass outside of Wimborne Town FC, where he is now general manager (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

“It’s very important at Wimborne [compared to a professional club] as it’s the education side that pays for the academy. In reality, the education side is an add-on even though I’m sure Tony told you different.”

Jimmy Glass and Tony Pulis are friends, having known each other since 1995 when Jimmy signed for Tony’s Gillingham side. So, what does he think of his former managers proposals?

“Tony is a smart guy who has spent his life in football. No one knows football better than Tony. What he’s saying will be essentially right.

“There are two ways to look at it; football needs to help these youngsters because it builds them up and creates expectation and hope but, generally speaking, they won’t make it through to the first team and get cut loose. What happens to them then should be thought about more.

“But by that time [they’re released] they’re 18-years-old and adults, the same way the schooling system might bring them all the way through, fail them and cut them loose at 18.

“In truth though you’d be setting 99.9% up for a backup plan and that would take a lot of effort and money. I doubt the clubs would be doing that themselves, so maybe it’s something the FA needs to look at and make the clubs adhere to.”

Jimmy Glass (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Jimmy Glass (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Jimmy, 51, is now using his wealth of experience to build Wimborne’s profile and develop its academy.

“The academy system is going well, and I think that represents the ideals of Wimborne Town, which is to be a wholesome, sustainable, community friendly club, where someone could come in at seven-years-old and come all the way through to play in our first team.

“My goals, and the boards goals, is to try and create two or three players a season that will go through the academy and into the pathway.”

‘It’s a personal choice.’

AFC Bournemouth have experienced rapid growth over the past decade and have spent a lot of time and money developing their academy. One of their brightest young stars, striker Jonny Stuttle, 19, believes a backup plan is essential.

AFC Bournemouth youth striker, Jonny Stuttle (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

AFC Bournemouth youth striker, Jonny Stuttle (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

“A lot of people frown upon it, but I’ve planned my life outside of football because you never know what could happen; I could get released in a year, I could get injured tomorrow and that could be it, so I think you do need something to fall back on.

“The club have helped massively with a backup plan; they’ve come in with workshops and exterior hobbies outside of football which is something I’ve always been big on.”

Jonny Stuttle playing for the AFC Bournemouth Development Squad (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Jonny Stuttle playing for the AFC Bournemouth Development Squad (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Sitting in the manager’s office after scoring in a 4-1 win over Watford U21s in the Professional Development League, Jonny has seen first-hand the development of a club he’s been at since 11-years-old. However, is he an anomaly by having a backup plan?

“I think it’s a personal choice. After completing my BTEC, I’ve done optional extras and I’m currently doing one in marine biology because you never know what could happen.

“You’ve done the base of something to fall back on, if you don’t want to do an extra add-on, then that’s up to you. They [the clubs] can’t force you to do anything, they’ve already offered us more courses which I took up on.

“A lot of people view it as a negative thing [having a backup plan], because they might think you’re not fully focused on the football, but I think you need to have that balance.”

The Future?

Despite being a shining star in the Cherries academy, Jonny Stuttle has thought about his future and has put plans into place. However, with clubs unable to force a backup plan upon those within the academy system, it’s unclear how many of the current crop of 10-12,000 academy players are in the same position as Jonny.

Current Premier League education guidelines require a minimum of a BTEC in sport, but clubs, like AFC Bournemouth actively do, can offer extra courses which are optional for players to take up. These extras build upon what players learn during their BTEC and can include a gym instructor course to become a personal trainer, for example.

These extras should be seriously considered by those within the system, but they perhaps still wouldn’t have benefitted Josh Carmichael if he was coming through today. Can more apprenticeship or practical courses be offered to help cater for those who don’t want to use their BTEC in sport? JP Morgan offers a professional athlete training programme where they train you for six months to gain the skills to potentially land a job afterwards, should more courses such as this be adopted?

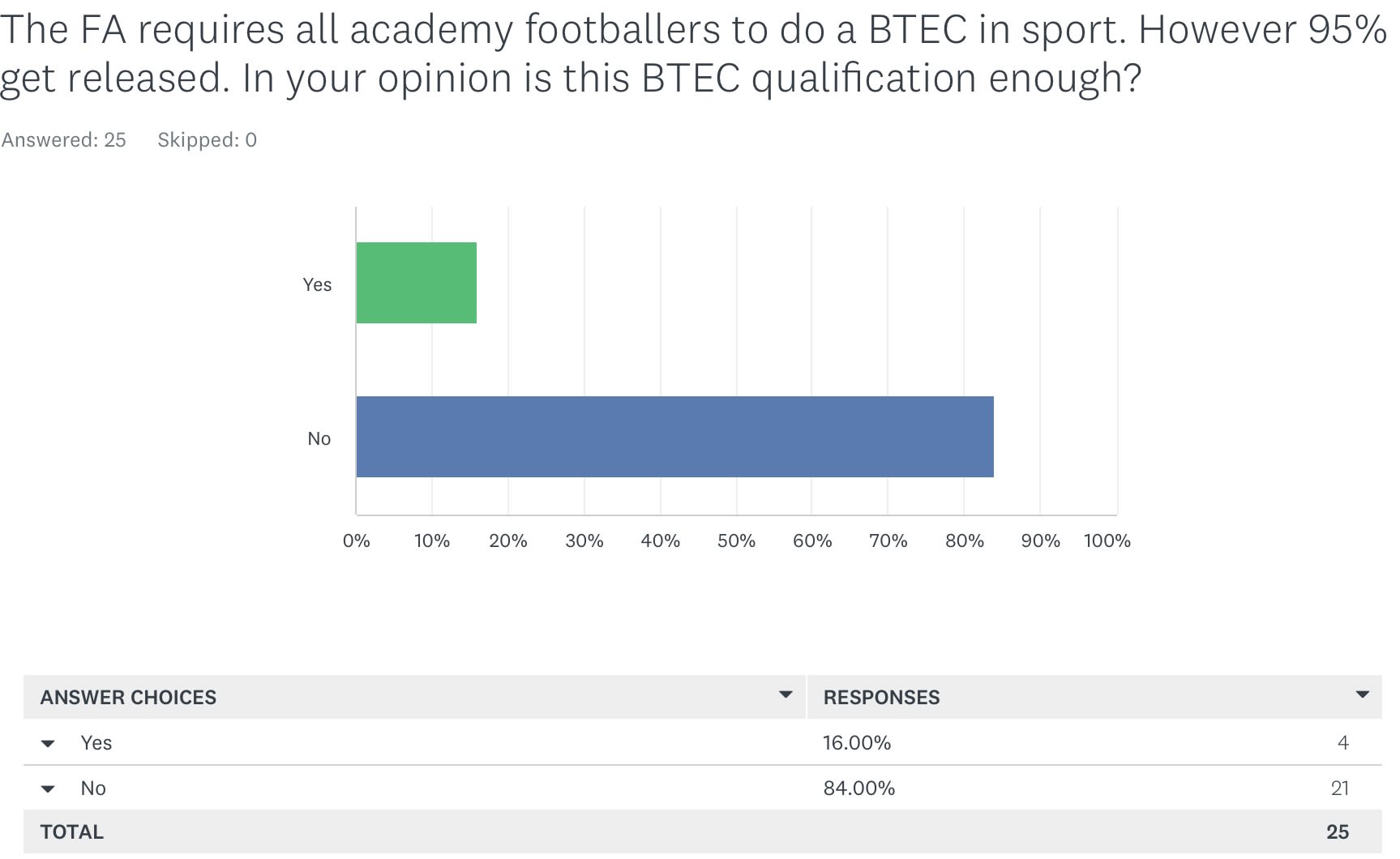

Data from my survey showed 84% of respondents believe a BTEC qualification isn't enough (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Data from my survey showed 84% of respondents believe a BTEC qualification isn't enough (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

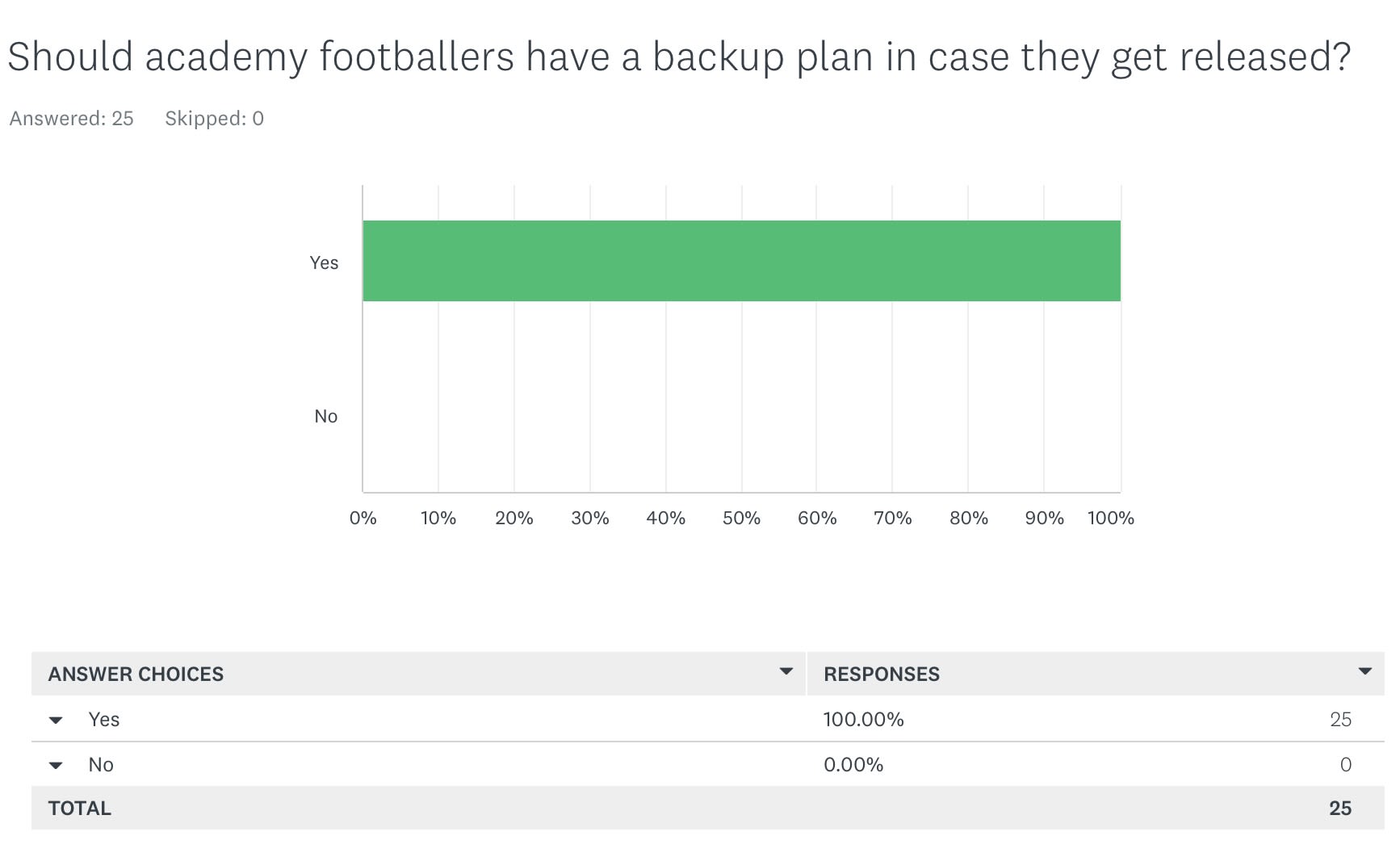

Data from a survey I created revealed that, despite the small sample size; 84% of respondents believe a BTEC isn’t sufficient and 100% believe backup plans should be implemented. However, whose responsibility should it be to create a backup plan? Arguments could be made for the clubs, the FA or the individual player, but should it be a combination of all of them? As Jimmy Glass pointed out, creating an individual backup plan would cost a lot of money, so who should shoulder that burden?

Data from my survey showed 100% of respondents believe academy footballers should have a backup plan (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Data from my survey showed 100% of respondents believe academy footballers should have a backup plan (Photo by Kyran Rickman)

Academy football’s future could be complex and it’s important that those in power get it right. Is the answer within Tony Pulis’s proposal of a dual-scholarship programme funded by the Premier League but run by an independent body that focuses on preparation for an alternative career? Time will tell whether the FA adopts it.