The fast fashion disconnect: Why we know better but don't shop better

By Grace Kehoe

Fast fashion dominated headlines in 2022, but as the market explodes toward $318 billion by 2032 (Fortune Business Insights), local experts say the gap between awareness and action has never been wider.

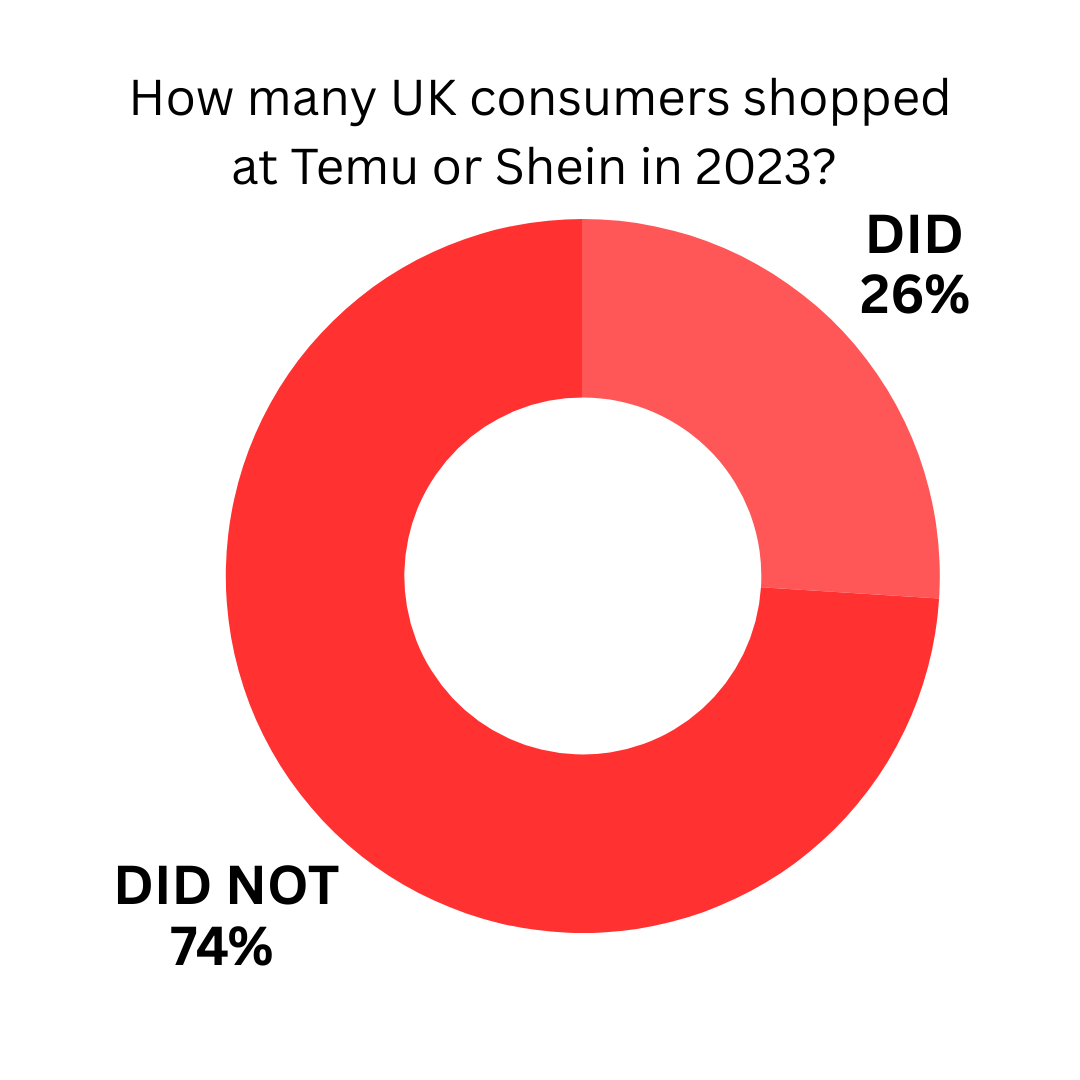

The numbers tell a stark story: clothing is now worn only 7 to 10 times before being discarded, a 35% decline in just 15 years (Uniform Market). At its peak in 2021, retail giant Shein released up to 10,000 new styles daily. And despite growing environmental concern, 26% of UK consumers shopped at fast fashion giants Shein or Temu in 2023 (The State of Fashion 2024 report).

The idea of fast fashion is not a new one, in a world where populations are chronically online and aware of their environmental impacts, retail consumer habits don’t reflect ethical decision making.

For students and shoppers on a budget, the appeal is obvious. It's cheap, it's easy, and it's everywhere on the high street and online.

But Bournemouth University researchers say this convenience comes at a cost that few truly understand and changing consumer behaviour will require more than just awareness.

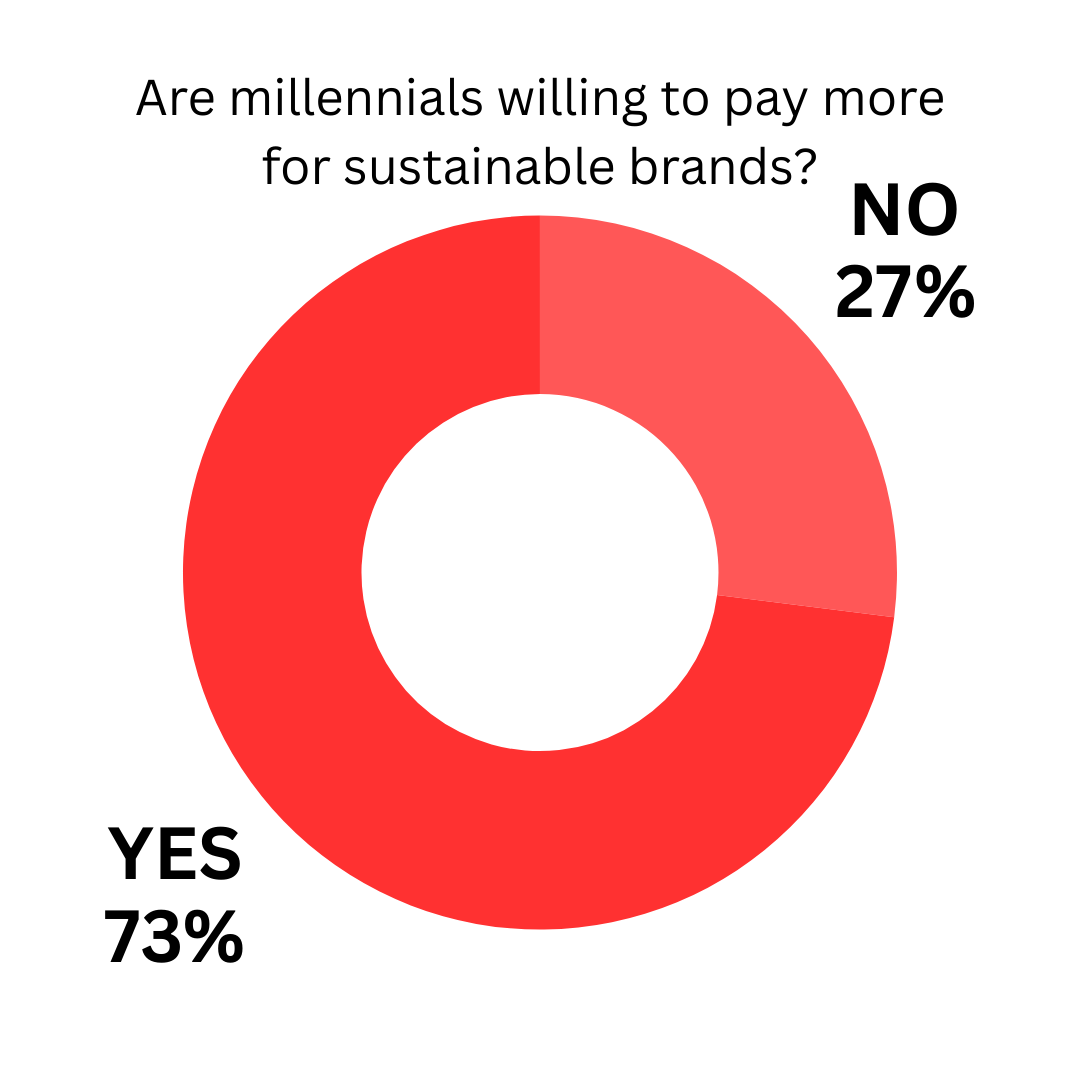

Infographic by Grace Kehoe (source: The Roundup)

Infographic by Grace Kehoe (source: The Roundup)

Infographic by Grace Kehoe (source: The State of Fashion 2024 report, published by The Business of Fashion and McKinsey)

Infographic by Grace Kehoe (source: The State of Fashion 2024 report, published by The Business of Fashion and McKinsey)

The education gap

Professor Marcjanna Augustyn, who chairs BU's Centre for Sustainable Business Transformations, conducted research with a small sample of her students that revealed a troubling pattern: those on a budget turn first to fast fashion and are most likely to dispose of clothes in unsuitable bins.

"One of our findings at the roundtable was that there is an urgent need for educating the consumer," said Augustyn, who presented on sustainable fashion consumption at a November 2024 roundtable in Tunisia. "Education plays a very significant role."

The professor argues there needs to be more awareness about what to do with unwanted clothes. That they shouldn't be thrown in the bin, but recycled, donated to charity shops, or resold if in good condition.

Marketing professor Kaouther Kooli, who co-chaired the Tunisia panel, toured the textile manufacturing plant that supplies Hugo Boss, Ralph Lauren, and other European luxury brands in 2025. She was impressed by sustainability efforts, finding that the facility purifies 80% of production water back to drinkable standards.

"Decision makers are doing a lot of work, but looking at other actors in the textile and clothing ecosystem, are they keeping pace with these regulatory changes?" Kooli said. "Maybe big players yes, they have the resources to adapt quickly. But small businesses, are they ready?"

With the 'Digital Product Passport' legislation coming into force in 2027, requiring detailed sustainability information for textile products, the pressure is mounting.

"Consumers are a very important player in this value chain,"Kooli added.

"There's a need to make all these actors play the same game and sing to the same rhythm."

Following my conversation with them, both professors began discussing how Bournemouth University itself could increase students' education on sustainable clothing consumption. A strategy that could have a significant effect on a large student population and their consumption habits.

The local alternative

For Studio Sal founder Sal, 39, the solution has always been clear: buy second-hand.

A vintage clothing enthusiast since her teenage years, Sal spent years collecting pieces in her attic, dreaming of opening her own shop. That dream became reality in 2024, but the physical retail space proved unsustainable. In 2025, she moved her enterprise fully digital, building her Instagram following while promoting sustainable wardrobe choices.

She started her Instagram page two years ago, where she shows off her vintage outfits and spreads some second-hand love.

"Vintage pieces are just so well made, there was thought put into them," Sal said. "People didn't buy as many clothes back then. They bought less clothes, and the clothes are built to last."

Second Hand Sal (Credit: Studio Sal)

Second Hand Sal (Credit: Studio Sal)

But she acknowledges the barriers. Sizing remains a major challenge because vintage sizing doesn't match current standards, making charity shop shopping particularly difficult for petite, plus-size, short, and tall shoppers who can usually find their size on the high street with more ease.

"Even when I had my own vintage shop, sizing was a barrier," Sal admitted. Clothes are supposed to make people feel good, elevated and happy. Leaving a store where you had no luck finding something in your size, you'd feel a little bit less confident she said.

The smell and "pre-loved" nature of charity shop items also puts people off. "A lot of my friends would not set foot in a charity shop," Sal said, even some refused to visit her own shop for this reason.

Still, she's frustrated by throwaway culture. "It annoys me, people are just so 'throw away' with things. People are using charity shops like a dumping ground these days."

Making the switch

For those wanting to transition out of fast fashion, Sal offers practical advice: "Go into the high street shops, see what you do like and learn your own style, but then go to the charity shops, go on Vinted." It’s all about pushing yourself out of your comfort zone and expanding your wardrobe.

She recommends taking charity shop browsing one section at a time and not looking at sizes. Focus on items that look good and feel comfortable rather than what the label says.

"Even if it's just one thing, it helps," Sal said.

Major retailers have launched initiatives to address the problem. H&M's Garment Collecting program has gathered over 172,000 tonnes of pre-loved clothing and textiles since 2013, on their website it says: “Through collecting, sorting, reselling, repurposing and recycling, we can give many of these items a second life.” They also reward members with a £5 digital voucher and 20 member points for bringing in unwanted items.

Clothes recycling bins can be found dotted around Dorset pavements or at household waste recycling centres in Wareham, Swanage, Weymouth, Portland, Wimborne and Dorchester.

Bournemouth University do not offer any clothes recycling bins currently, but the student union (SUBU) run an event called The Big Give, a charity donation drive. This scheme runs from May until September and in 2024 the charity effort gathered 4765 bags of unwanted clothing, accessories and household items.

The market reality

Despite growing awareness, the sustainable fashion industry faces an uphill battle. While the sector is forecast to reach $15 billion by 2030 with an annual growth rate of 8.3%. But compare this to fast fashion's trajectory from $162.76 billion in 2025 to a projected $317.98 billion by 2032. The differences are astronomical.

Research published by The Roundup shows 73% of Millennials say they're willing to pay more for sustainable brands. Women under 35 remain the largest target demographic for fast fashion retailers.

The question isn't whether consumers know about the environmental impact. It's whether they'll act on that knowledge when faced with the convenience and affordability of fast fashion.

As Kooli put it: getting everyone to "sing to the same rhythm" may be the industry's biggest challenge yet.